Why Sailors Should Be Considered in the Rigorous Selection for Astronaut Jobs

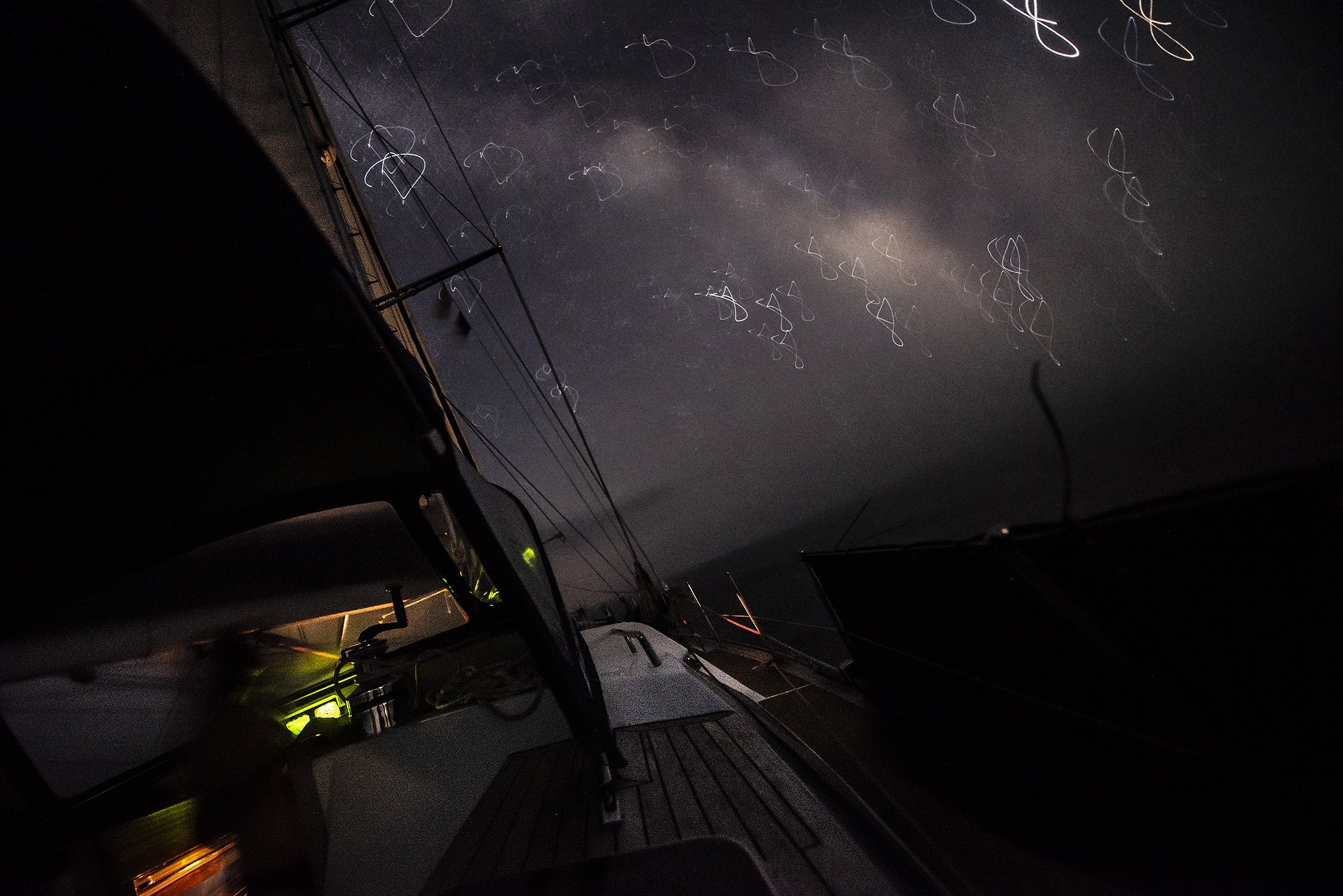

There was an unforgettable moment in my life during a lonely night watch aboard a 50-foot expedition sailboat, enveloped in pure darkness. But the truth is… it was never really dark!. I was so stunned to see how bright and immense the stars appeared in such clean, unpolluted air. And then I noticed something else: the ocean is shining in the dark! Each time the boat bounced, it stirred up bursts of glowing bioluminescence, glittering like electric shockwaves across the water.

Then came the shooting stars.

I navigated by the constellations, reading the sky to understand our direction. And in that moment, I imagined myself not on Earth, but being adrift in space.

It was the closest sensation I’ve ever had to being in the Universe.

On one peaceful day at sea, with the ocean calm as a cashmere blanket, I sat down to write my application to the European Space Agency, which had opened astronaut positions. I had been researching for months—digging deep into the requirements, the diversity of roles, the specializations, and the stories of those selected.

Pilots, engineers, scientists, mathematicians…

I couldn’t help but kept wondering: how does one go from office-bound work and a year of astronaut training, then embark what we sailors call the offshore life? That moment when the vessel leaves port and enters the void—just like a spacecraft leaving Earth. After crossing 800 nautical miles, there is no return. Even in harsh latitudes, a “MAYDAY” is unlikely to bring help. You’re alone with your crew, your vessel, and whatever comes…!

I often imagined how astronauts must feel crossing their own “point of no return”—strapped in, countdown ticking, the spacecraft launching into the silence of space for a long, slow, and often monotonous journey.

It’s far more monotonous than we imagine.

From the outside, all we see are the dramatic photos: the excitement, the adventure. But that thrill, I suspect, lasts only for ten minutes. What follows is the reality: isolation, repetition, and the need for absolute resilience. I read somewhere that in space, time even seems to pass more slowly. There is no quitting if you're not feeling well—physically, mentally, or emotionally. Harmony within the crew is not optional; it’s critical.

I've crewed nearly a hundred people on various sailing expeditions - CEOs, scientists, elite athletes, artists, teachers - and I've seen the full spectrum of human behaviour in extreme environments. What I’ve learned is that success out there doesn’t depend on titles or resumes. It depends on being humble, adaptable, and easygoing. And for someone like me, with ADHD, no other experience has prepared me for this kind of resilience and adaptive better than my time crossing oceans.

Seasickness in zero gravity? Absolutely. Astronauts have written about it. But like with sailing, you never know who will be affected, or how long it will last—until you're already out there.

In my crews, the people with the highest positions often struggled the most with adaptation. The ocean doesn't care who you are. It just is.

My astronaut application only made it through one stage. I don’t have a scientific degree, so it was no surprise. Still, I was determined to try. I wrote passionately—arguing why someone like me should be considered. I consulted others. I worked on that application for months.

And so, here we are!

Let’s look at the case again. A captain accredited with a USCG Master’s license or Yachtmaster certification, someone who has sailed thousands of miles across the world’s oceans, leading crews through every imaginable configuration and challenge—should be an option in the astronaut selection process.

Here’s why:

The ocean is Earth’s closest analogue to space—a vast, hostile environment where humans must survive with the help of life-supporting vessels.

Sailors are excellent divers. They’ve mastered neutral buoyancy—an essential training tool for astronauts learning to move and work in zero gravity.

Offshore captains manage teams in complete isolation, where external help is not an option. Leadership is earned, not given, and humility is constantly practiced.

They are critical problem-solvers. Even without formal engineering degrees, sailors routinely diagnose and fix complex mechanical, electrical, and structural issues. A broken system offshore is life-threatening—just like in space.

Celestial navigation is second nature. Sailors know how to read the stars—not just admire them.

They are trained for long, understimulating voyages, where time slows down, and the only rhythm is dictated by the elements. Sleep cycles adapt. The body learns patience. The mind sharpens.

Yachtsmen exhibit rare wisdom, resilience, and creativity—the kind forged not in classrooms, but in storms, doldrums, and months at sea.

My point is this: the figure of a sailor is someone who is naturally prepared for isolation, responsibility, unpredictability, and monotony—key challenges in spaceflight. In fact, I believe that in many ways, sailors can accelerate the adaptation process and contribute to a diverse and capable astronaut corps.

So why not include Maritime Captains in the selection pool?

What do you think?